With February being Black History Month, the overlap of race, stigma, and substance use disorder seemed an appropriate topic.

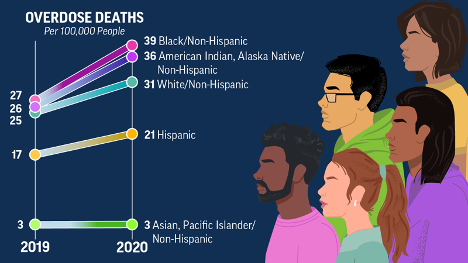

Drug misuse, overdose deaths, and incarceration rates due to drug misuse disproportionately affect BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) individuals and communities (1). Overdose death rates have increased for all races, but disproportionately so. The highest from 2019 – 2020 are seen in Black (44%) populations, with older Black men being 7 times more at risk of dying from overdose than older White men. American Indian and Alaskan Native populations had the second highest overdose death rate increase with 39% (2). There are a lot of reasons for this imbalance.

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) development and race:

Research suggests individuals categorized as BIPOC receive more everyday stress due to systemic racism and other societal imbalances. These individuals are also more likely to grow up in a home environment with less amenities and access to mental health help, affordable healthy foods, and adequate healthcare (3).

Due to overall higher risk factors in these populations, individuals are more likely to start using substances at a younger age, which makes them more likely to develop substance use disorders as adults. Compounding that with continued lack of access to treatment options nearby like recovery centers and MOUD (Medications for Opioid Use Disorder—formerly MAT, “Medically Assisted Treatment”), combined with increased stigma for using, the issue perpetuates. Black and brown people are more likely to be stigmatized by individuals in healthcare settings, which affects their immediate care and access to future care (3). They’re also more likely to be turned away from recovery centers earlier. SAMHSA recently reported 18.6% and 17.6% of Black and Hispanic individuals respectively receive illicit SUD treatment compared to 23.5% of whites (4).

A recent study talked about access to MOUD and the disparities between races. Buprenorphine is one treatment option and is a prescription drug that can be filled at pharmacies and taken in everyday, unsupervised settings. This medication is overwhelmingly prescribed to white, middle-class individuals. Methadone is another option for MOUD, and is often the option to BIPOC populations, but requires medical administration and monitoring with every single dose (5). This inequity in access to necessary care further perpetuates the imbalance.

When we think about substance use disorders, including opioid use disorder and alcohol use disorder, our society sees this as a short-term illness, when in reality, we know it’s a chronic condition like any other. Individuals with hypertension or diabetes are treated for those conditions their entire life and wouldn’t be expected to “get better” after one doctor’s visit. They receive ongoing medication and counseling, and so should be the case for individuals with SUDs.

The solution:

This is a complex issue, as are many related to SUDs and inequity and will not be fixed overnight. Some potential solutions to move in the right direction are to speak up about the imbalance of care and access to care for marginalized communities. Solutions include trying to combat stigma related to SUDs as a whole, but also specifically within these populations, and being aware that these issues affect people in different ways.

The good news is there are certain programs trying to offset this imbalance, like REACH (Recognizing and Eliminating disparities in Addiction through Culturally informed Healthcare), a program funded by SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). ACCESS (Achieving Culturally Competent and Equitable Substance use Services) is another program specifically targeting the co-occurrence of SUDs and mental health illnesses in diverse patients (6).

The increased number of community health workers also aims to shift the imbalance, by addressing SUD care and mental health care in the field and removing a barrier to treatment and care. A growing number of Certified Behavioral Health Clinics, which receive Medicaid reimbursement, could help reduce the divide with this issue (3).

References:

- Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mulia N, et al. The future of research on alcohol-related dis- parities across U.S. racial/ethnic groups: a plan of attack. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(1):7- 21. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.7 PMID:29227222

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Drug Overdose Deaths Rise, Disparities Widen.” 19July2022.https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/overdose-death-disparities/index.html.

- Ghoshal M. “Race and Addiction: How Bias and Stigma Affect Treatment Access and Outcomes.” Psycom Pro. 17Nov21. https://pro.psycom.net/special_reports/bipoc-mental-health-awareness-racism-in-psychiatry/race-and-addiction-treatment-outcomes

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2021). Racial/ethnic differences in substance use, substance use disorders, and substance use treatment utilization among people aged 12 or older (2015-2019) (Publication No. PEP21-07-01-001). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https:// www.samhsa.gov/data/).

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ. Addressing racial & socioeconomic disparities in access to medications for opioid use disorder amid COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 24]. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;108214. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108214

- Gardner C. Yale School of Medicine. “Racial Inequities in Treatments of Addictive Disorders.” 01Oct2021. https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/racial-inequities-in-treatments-of-addictive-disorders/